When protection becomes pressure

Police officers are expected to prevent crime, respond to emergencies, safeguard vulnerable people, investigate complex offences, manage public order, and maintain public confidence — often simultaneously. Behind this broad remit sits a reality that is increasingly difficult to ignore: many officers are chronically overworked, operating under sustained pressure that exceeds realistic human capacity. This is not a question of commitment or professionalism. It is a question of system design.

Demand has increased — and changed

Modern policing demand now includes mental health crisis response, safeguarding, domestic abuse risk management, missing persons investigations, digital crime, and multi‑agency coordination. These duties are time‑intensive and emotionally demanding, even where no criminal charge follows.

Staffing levels and abstraction

Headline officer numbers often obscure frontline reality. Officers are abstracted for custody, hospital watches, court attendance, training, and to cover shortages. Workload concentrates on fewer officers, creating a cycle of stress, sickness, and further abstraction.

Long hours and unpredictable shifts

Missed breaks, cancelled rest days, overtime, and sudden shift changes disrupt recovery. Chronic fatigue impairs attention, memory, emotional regulation, and judgement.

Administrative load

Safeguarding and accountability processes have expanded. Officers now spend significant time documenting decisions rather than making them, increasing cognitive load and the risk of error.

Cumulative exposure to trauma

Repeated exposure to violence, abuse, and sudden death without recovery time creates cumulative strain that affects concentration and decision‑making.

How overwork increases the risk of mistakes

Fatigue and cognitive overload increase reliance on shortcuts, reduce error detection, and encourage defensive decision‑making. Rushed risk assessments and administrative errors become more likely under sustained pressure.

What the evidence shows

Across safety‑critical professions, evidence shows fatigue, high workload, and abstraction increase error risk regardless of training or experience.

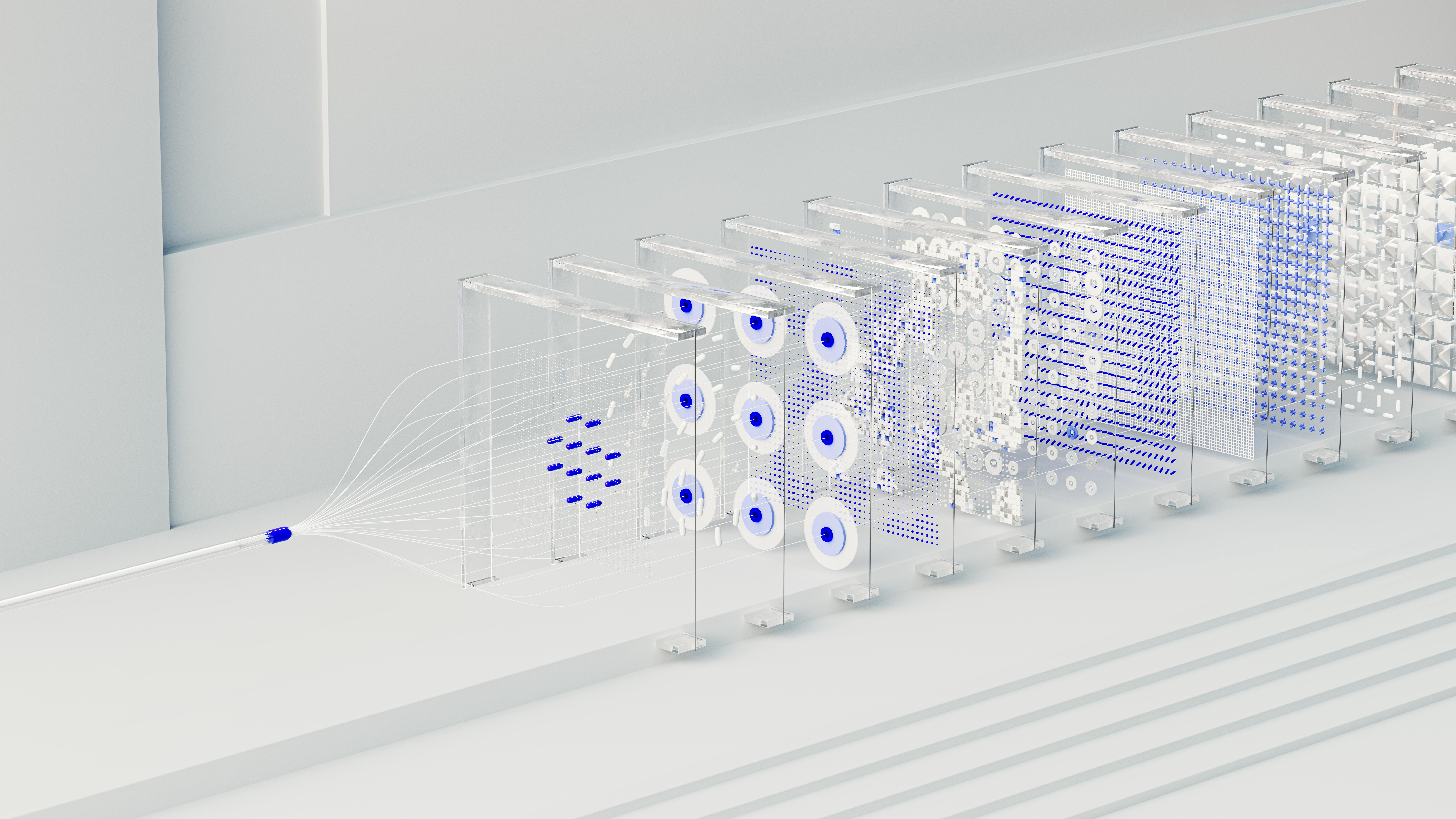

How system design creates error

Demand is unlimited while capacity is fixed. Processes expand without subtraction. Retrospective scrutiny often ignores real‑time operating conditions. Resilience is treated as a substitute for capacity.

Conclusion

When overload is constant, mistakes become predictable system outcomes. Demand is effectively unlimited while capacity remains fixed, processes expand without subtraction, and retrospective scrutiny often overlooks the real-time conditions in which decisions are made. In this context, resilience is too often treated as a substitute for capacity. Reducing error and harm therefore requires attention to system design and operating conditions, not solely individual accountability.

This article forms part of a wider series examining how workload and system design shape decision-making across social care, policing, courts, and technology-driven systems.